On Launching the Argo

Part Three on the Allegory in the Orphic Argonautica

This is Part Three of an ongoing series. You can read Part One here and Part Two here.

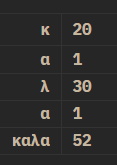

Counting Orpheus and Jason, there are fifty-two men among the Argo’s crew in the Orphic Argonautica. This is not by coincidence: there are also fifty-two weeks in the year (and even though this poem is ancient, it is believed to be younger than the adoption of the seven-day week in the Roman Empire). As previously argued, the Year can be seen as a cycle of purification and also a microcosm of the Soul’s ascent.

Furthermore, in Platonic thought, The One (i.e. the ultimate source of everything) is also called The Good, and equated with the Form of Beauty. Using isopsephy, also widely used at the time the poem was written, we find that fifty-two is the sum of the word καλα, which is a plural word meaning “beautiful things” (sometimes translated as “noble deeds” to avoid the association with physical appearance).

Thus, our Argonauts as a single whole represent the cyclical purifications undergone by the Soul and also the specific beautiful things which it must acquire/refine. Though, as evidenced by the word καλα, they are still plural (i.e. Many) and not yet The One/Good beyond everything else, i.e. “Beauty Itself” (καλον). To achieve that, they must complete their quest for the Golden Fleece.

Dying to Start

Briefly though, between introducing the Heroes and launching the Argo, our poet tells us that these men gathered together at a single, long table to eat a dinner they’d prepared, “each of them dying to start their work”1. In the very next sentence, their hunger is satisfied and they stand up, eager to leave. It is no mistake that this should all take place in a single paragraph that exists to bridge what has come before and what will come next.

Before, we were getting acquainted with the various faculties of the Soul, or the various beautiful things that one’s Soul must cultivate in order to retrieve the reward. This liminal paragraph, though, especially because of that earlier quote, “each of them dying to start”, signifies that everything before this point was preparation: one must die for the Soul’s journey to truly start.

Launching the Argo

With the feast signifying death, and the Argonauts’ hunger sated, the crew heads to the ship. Most of the crew, upon seeing the ship, were awestruck and stood staring. “Argos, however, obeying the commands of his intellect, prepared to heave it up by means of wooden trunks and well-twisted ropes fastened to the stern”2. In Part One, it was said that Argos, as the ship’s architect, represents skill and the capacity to execute ideas. The Argo, as the ship that will carry all of these Heroes, represents the vehicle of the Soul.

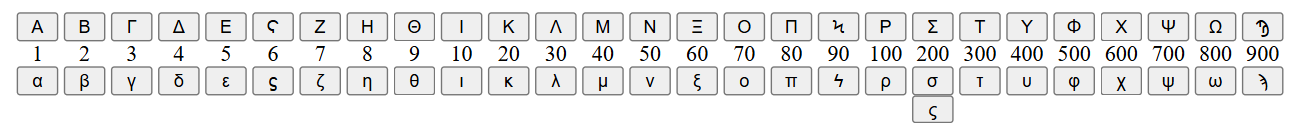

In designing and building the ship, Argos was guided by Athena, a Goddess of wisdom and strategy. Here in launching it, he obeys his intellect, which we are told by Proclus “is Dionysian and truly an image of Dionysus”3. Macrobius, who variously quotes Orpheus in his syncretism of Apollo and Dionysus (and others) together as expressions of the Sun, says that “for the physicists Dionysus is ‘the mind of Zeus’ (Διὸς νοῦς)”4 and a few lines later he specifically says that Euboleus (meaning “good counsel”) is an Orphic epithet for the Sun5. These two authors are roughly contemporaneous to the believed date of Orpheus’ Argonautika6, lending further credence that all three were drawing from the same pool of belief.

These teachings may even be traceable to the Derveni Papyrus: its anonymous author is the earliest to quote Orphic poetry and, as such, the first to do so in a broad syncretization of all deities into one (like Macrobius much later), showing that this remained a central piece of Orphism for roughly a thousand years7.

So, more than just a generic capacity to execute skill and ideas, Argos’ skills and ideas are divine in origin, and he alone among the Soul’s faculties remains sure in the immediate wonder that follows one’s death. This, perhaps, is why the philosopher-initiate must spend their whole life in preparation: so that, even in these moments of overwhelming wonder, the Soul’s inner Argos may remain in-tune.

We are told next that Argos “called on everyone and exhorted them to get to work, and they obeyed eagerly”8, removing their armor, tying ropes around their chest to pull the ship, and marching forward toward the sea. The Argo was stuck, however, held fast by dry seaweed and refusing to move. This shows that, no matter how practiced one may be, you cannot “brute force” enlightenment.